© Robert Barry

Francos / FFanzeen, 1981/2022

Images from the Internet unless indicated

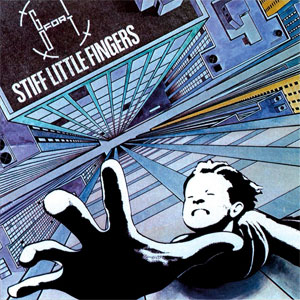

Bassist Ali McMordie in the forefront

One of the

great and little-known aspects about Irving Plaza in New York during the 1980s

was that the back door was not only open, but unguarded until a couple of hours

before a show. While I didn’t often take advantage just to see free shows by hanging

around, settling down for a long wait (and not wanting the management to become

aware of the situation, killing the golden goose), I did occasionally use this

knowledge to gain access to bands that were playing at the club.

Alan

Abramowitz and I went through the back door one late afternoon and caught the

Stiff Little Fingers soundcheck. After, we approached the band about the possibility

of an interview. The only SLF member who did not have a previous appointed

place to be was Ali McMordie, the bass player, and we propositioned him. Ali

agreed to the interview, which we did upstairs in the Irving Plaza dressing

room.

This interview was published in FFanzeen, No 8, dated 1981.

Stiff Little Fingers: Wait and See

I am not one to extol the virtues of the new music coming out of England right now. When the punk movement died and the Blitz and New Romanticism fashions came in, my interest sort of declined. The better groups still seem to be the older ones, like Buzzcocks and the Jam.

About a year ago, a friend came

to me telling of a great new song he’d heard called “At the Edge,” by some

group called Stiff Little Fingers (named after a song by the Vibrators). When I saw a copy of SLF’s Nobody’s Heroes in a cut-out bin, the album on which the song appeared, I figured

what-the-hell. And I’m damned glad I did.

Stiff Little Fingers has

been around quite a while now –since the mid-punk days of late ’77. Their first

album, Inflammable Material, is a social comment, as well as a musical one. A rare, successful

cross between the power of the music of the Ramones and the biting lyrics of

the Pistols.

The band’s four members –

Jake Burns, guitar and lead vocals; Henry Cluney, guitar and vocals; Ali McMordie,

bass guitar; and Jim Reilly, drums, replacing Brian Faloon after the first

album – hail from strife-ridden Belfast, and have since moved to London to help

their careers (Henry, however, chose to remain a resident of Belfast) – which has

been going full-guns since Nobody’s Heroes was released. From the time I first started listening, two more albums

have followed: the live Hanx (Irish slang for “thanks”), and the recently released Go For It.

I caught up to the band when they appeared in New York City on a cross-American/Canadian tour. The following interview was done upstairs at Club 57/Irving Plaza, on June 20, 1981, with bassist Ali.

FFanzeen: Where do you head from

here?

Ali(stair) McMordie: I wish I knew. I don’t know the exact dates, still. It’s

always the same any time we come over here because to organize anything in the States,

you actually have to be in the States. You can’t do it on the phone because it just takes too

long and nobody bothers calling you back. We sent our manager over two days earlier

than us to do that, specifically. We’re going to both coasts and Canada. Last

tour we just did the two coasts.

FFanzeen: When

the group first started, I read that you rented out your own gigs, and then

sold tickets on the sly.

Ali: Yeah, because any time we booked a club, there were some places that were

really cheap, like $20 for a night. The club made its money on the bar, and of

course, you weren’t allowed to sell tickets because that would mean you’d be

making quite a bit of money. So, we’d sell them for 60p; that’s less than $2

anyway. We sold them at the carpark outside so the management couldn’t see us.

We used to give them to record shops to give to people or to sell. We never got

our money back anyway, so after a while we Just let people come in for nothing

to try and fill up the place. It was pretty hard in Belfast, finding clubs;

there weren’t that many. There were only about two clubs left in those days.

FFanzeen:

There’s a large music scene growing out of Belfast now.

Ali: There’s a lot of bands there, right.

FFanzeen: The

Undertones, Protex –

Ali: Protex, yeah. They’re based in London, right now. They did okay over here.

Not as far as records go, though.

FFanzeen: They

played a lot of gigs here.

Ali: Back in Belfast, we played our first gig of the tour. You’ve heard of the

recession over in England, nobody’s got any money? It’s crazy. Out of all the

towns, they’re hardest hit in England, up north there, Belfast being in it as

well. But we really enjoyed being back there; part of the fact that it’s our

home town, they don’t bother much about worrying about the recession because

they’ve got so much else to worry about.

[Ali leaves to get cigarettes, then returns]

FFanzeen: According

to the souvenir books at your concerts, the band has, “always done things the

hard way.” How true is that when your first single [independently released “Suspect

Device” b/w “Wasted Life,” on Rigid Digits Records – RBF, 1981] sold over

30,000 copies?

Ali: The first sold about 60,000 so far. I know what they mean about making it

the hard way. I think we were very lucky to start off with. We brought the

first single out, and the two guys managing us, Gordon Ogilvie and Colin

McClelland, took the single an sent it off to (London DJ) John Peel, and thanks

to him, basically, people heard the single and picked up on the band. And from

then on it was pretty plain sailing. We were sucked into the big music

business, where so many things are hyped. Over here, it’s not how good a band

is, it’s how much money their management has. Over in England, it’s not quite

that bad. I was talking about this earlier when we first came to London, we

didn’t really know our way about. We didn’t know anyone over there. It was

quite a big move from Belfast, across the sea. We joined Rough Trade and that

gave us a kind of breathing space where we could sit back and look at things

objectively, detached. We could see that record companies weren’t as they were

cracked up to be. Our first experience with record companies was Island Record,

and from that we said, “Fuck this, we don’t want any part of it.” So, we put

the record out with Rough Trade and a couple of singles, and just took our time

with lots of offers from record companies, but we waited until we could get a

deal where we could virtually tell them what we wanted instead of it being the

other way around. And Chrysalis did it. In the U.K., we got complete control.

We didn’t get any advance or anything because that’s not important, it’s only money.

We deal with the record company and we’re in the black. Which is good. Most

bands work heavily in the red, like the Clash. They’re so much in debt that

they’ll be tied to CBS for as long as CBS wants ‘em. You have no control of

your lives, virtually. It gets to that stage. New York pays a lot of money. For

the gig we’re doin’ here – I don’t know what it is, exactly – but they’re

giving us all the money and we could easily just do a lot of gigs here and then

piss off and make a profit. Instead, we’re just using the money to go to other

places around the States and up to Canada. Most of the clubs here seem to jump

at anything.

FFanzeen: As

long as you’re from England, you can get plenty of gigs here.

Ali: Japan’s just like that. I haven’t been there yet.

FFanzeen: Your

booklet also called you “exploiters of Northern Ireland’s troubles.” They seem

to rip into you as much as compliment you.

Ali: That’s pretty close to the truth, though. They’re not saying we’re cynical

exploiters, they’re saying that’s what we’ve been called.

FFanzeen:

Well, why have you been called

that?

Ali: I don’t know; we’re not cynical. I don’t see how we can exploit Northern Ireland

since we come from there. On the first album, there actually is only about four

songs on there about Northern Ireland. The rest of them could apply to any

place. There are as many songs about the troubles as there were about the fact

that there was a fuck-all attitude in Belfast. That’s why the band came about,

because it was a hobby, something to do on a Saturday afternoon. And a place

like that, you look for your own entertainment or you really have to go out and

search for it. Here (in New York), you go two blocks and there is something

there. It’s completely different. We were the top acclaim as rebel heroes, yet

with the first album, the reviews that Inflammable

Material got in the British press, they were very

good. They were all five-star reviews of over the top, which meant it got a lot

of publicity and all that, and that’s something that’s hard to live up to. One

of the main reasons why that was so, is because at the time, people were

getting fed up. It was just about the time of the demise of the original punk

bands, and people were looking for something new. We came along and they said, “At

last, a real punk band.” We took no claims to what kind of band we are. We just

play rock’n’roll.

FFanzeen:

Yeah, but you’ve been around just as long as they have [1977].

Ali: Yeah, but most of the time we spent rehearsing in Ireland. We just had a

couple of gigs here and there. We were always pretty much apart from the rest

of the music scene. The Sex Pistols, Gen X, they all hung around and knew each

other. We came over and didn’t know anybody.

FFanzeen: Did

you find the move to London difficult to adjust to?

Ali: Not now; I did then. There’s a couple of songs written about it, like “Gotta

Getaway,” when we first came over from Belfast. The very first time was with

Island Records, and they fucked us about, so we just got fed up and decided to

move out on our own with no money and no support. Rough Trade was interested,

but that was all. There were five of us stuck in one dark hotel room in West

End Grove in West End, London, with no money, so we had to live off Gordon. Imagine

five of us – four guys in the band and one guy who was working with us – and the

arguments that went down. We couldn’t get out anywhere because there was no

money and we didn’t know anyone. There’s no way I’d like to see that again. In

that way, it’s been hard. We’ve been lucky, though, because it’s so much harder

for other bands. There’s so much competition. All it really takes is a lucky

break or lots of money. And no one’s got money now. Especially over there. It’s

a shame because there’s so many people I know who’re great musicians. Good

bands. They haven’t done that well. Even recorded bands; Sector 27 – I think

they’re excellent. That band’s really good, and I loved TRB [Tom Robinson Band] – but they’re not doing all that well.

FFanzeen: It

says here that you consider your new album as “punk.” Do you really think that

is accurate?

Ali: Call it what you want. It’s punk in that – well, what does the word “punk”

mean? It’s an attitude. Jake said that he said that punk is more an attitude

than a style of music. You know the Ruts? A lot of their music is more heavy-metal-oriented

than punk, but because of their attitude and their lyrics, and so on, they’re

considered a punk band.

FFanzeen: In

the fanzine Damaged Goods, they commented

that this past album is different from your previous albums, but I found it

very similar to the others, which is a quality I liked about it.

Ali: I don’t think it changed that much. There are a few things on the new

album that are pretty different. “Gate 49” is done tongue-in-cheek in

rockabilly style. It’s good fun playing that. There was an instrumental [“Go For It”]. It’s the second time we’ve done that. First time was “Bloody Dub” from

Nobody’s Heroes. That didn’t work very well. I think the “Go For It“ instrumental is a

lot better. That was written in the studio. There were supposed to be lyrics,

but we decided not to spoil it. The thing I like about the new album is – well,

what I like and don’t like – is that it was done in two weeks, in February and

March, and none of the songs were written before January. It’s just suddenly all

these ideas came together. Listening to it now, there’s a lot of things we

could have done – all these ideas and arrangements and so on – but maybe if we spent

a month doing it we could have lost that initial roughness and impact. I think

it’s a rougher album than Nobody’s Heroes. Who knows, we might put an album out in six years’ time that will be

like Inflammable Material. Kickin’ up a racket. It’s the sort of thing we regret three years ago.

It’s just different. We’re just playing songs that we like. There’s no way we

could be calculating about it. It’s impossible to figure out what people will

like. We just do what we do and hope people will like us. The new songs have

been doing okay so far. We were worried about it because where we come from, things

are so different. But fans that we’ve got, most of them are die-hard fans, and

they’ll always be there. The people who have come and gone are those who come in

and then go away because all they want to hear is “1-2-3-4” Ramones stereotypes.

Don’t want to get in a rut, now; it would get boring for everybody, including us.

That’s the first album over and over again.

FFanzeen: It’s

a bit passe now.

Ali: I don’t like to listen to it now. I think the songs off the first album we

do live, they’re a lot better than the album. But the thing is that it was

perfect at the time; that’s the way we felt. It was done really roughly. It’ll

be the same with every album – it’s the way we were, at the time. Times change,

so we still do the songs live, because they mean a lot to us.

FFanzeen: Are

you really heavily influenced by Marc Bolan [d. 1977], or is it just Henry [see

album covers]?

Ali: No, just Henry. Henry is in love with Marc Bolan. Necrophilia.

FFanzeen: What

about you?

Ali: We used to argue about it. Everyone’s tastes are completely different. We

can’t bother arguing because it’s pointless now. The first band that really

sort of influenced me was the Velvet Underground. I got back and discovered all

these great Velvet Underground records. From there, Iggy Pop and the Stooges,

things like that. Patti Smith, I think she’s great. The main bands are

American, but they’re not mainstream American. I’d even listen to some jazz-rock.

I like a lot of reggae. If any music influences, for me anyway, it’s reggae.

That’s one thing that we all like.

FFanzeen: Why

do you think reggae is such a big influence in England right now?

Ali: Mainly Bob Marley (d. 1981). Reggae has always been associated with punk,

since punk came along in ’77. I don’t know why it all came about, really. I

think they were supposed to share the same ideas, the same philosophy. I think

it’s that the rhythms of reggae are important, because it’s better dancing to

reggae than dancing to disco. Reggae has such a great beat, a distinctive rhythm.

[In a Jamaican accent:] Dat’s wot it’s all about, mon.

FFanzeen: Is

that the point of the song, “Roots, Radicals, Rockers and Reggae” [on the Go For It album]?

Ali: Have you heard the original? You should play the original. Its far better, obviously. We did it so

different. The original is about half the speed. It’s a brilliant single; Bunny

Wailer (d. 2021) brought it out. It’s on Island Records. If you ever get the chance

to hear it, it’s probably really hard to get over here. It’s pretty hard

getting it in England, but it’s a great song. That’s if you like reggae. It’s

like “Johnny Was.” That’s another great thing about reggae: you’ve got a lot of

space, a lot of freedom to be spontaneous. It’s different every night.

FFanzeen: As

the bass player, don’t you ever get tired of playing the same rhythm for

extended periods of time [on Inflammable Material, “Johnny Was” runs for 8:05, and on the live album Hanx, 10:15 – RBF, 1981]?

Ali: It’s not all the same. There are differences, but it’s very subtle. As the

bass player, I reckon there’s one difference in the song. Listen to it tonight.

It’s a lot shorter now, it’s only five or six minutes instead of ten. That went

on a bit long. Listen to the reggae break and you can hear the changes – I hope

[laughs]. Whenever I get home and listen to reggae or watch a band, the main

thing I get into is the rhythm. It doesn’t matter if it’s virtually the same

for five-ten minutes. The Velvet Underground’s “Sister Ray” had this rhythm going all the way through it – sort of mesmeric.

FFanzeen: Same

thing with Fred Smith’s bass line in Television’s “Little Johnny Jewel.”

Ali: I have that. On the original Ork label. In Belfast, it took about six

months to get it.

FFanzeen: A friend

of mine asked to ask you this: there is supposedly a video game called “Go For

It,” which has a boy climbing up the side of a building. Have you seen it?

Ali: A video game? No, [ours] has nothing to do with that. I’ve never seen it.

I’ll tell Gordon (Ogilvie). That’s the sort of thing he’d be really choked

about. Most people think the guy (on the cover) is falling off the top, but –

FFanzeen: – He’s

climbing up.

Ali: Originally, it was just that [covering up the right

side of the album cover that has the character’s arm and leg – RBF, 1981], which looks like he’s falling so the guy who was doing it works in

the creative department at Chrysalis in London added a knee and leg and arm

reaching up.

FFanzeen: Here’s

an original question: What do you think about the whole punk movement, then and

now?

Ali: The music then had a bit of energy to it. I suppose, looking back now, I’m

a lot more cynical than when the whole thing started. At the same time, I

believe in what we’re doing. I couldn’t get cynical about that. It’s funny

looking back at those early punk bands and to realize how shallow a lot of them

were. I think at any start in music, whatever point it is, it’s the second wave

of bands – heavy metal came along; Cream were pioneers, really, but they didn’t

last. It was Led Zeppelin who took over.

FFanzeen:

Unfortunately.

Ali: The Sex Pistols, the Damned – the Damned are still going, but that’s to be reckoned with. They’re like a comedy routine.

With the Sex Pistols gone, it’s just up to us to keep the plan flying. Punk

doesn’t have to be a noise. We’ve met a lot of very nice people – but now,

there’s beach punks. These guys come along, they’re wealthy with rich parents

and they can afford to have a beach of their own.

FFanzeen: You

know, with all the first wave bands changing and all, one of the things I like

about your band, as I said, is that you’ve been consistent. Not like in the

Clash who have gotten “glossy,” or the Ramones who have gone the way of Phil Spector.

Ali: I like what the Clash are doing now. I like the ideas that they’re trying

to do, and they are trying to break away. They’re trying to make it in America.

It really was a conscious decision. They’re doing it quite good enough. Their

reggae songs are not true reggae songs. You’d really have to come from Jamaica

to do real reggae. It’s just really an influence, a rhythm.

FFanzeen: Sort

of like the difference between the Police’s white reggae as opposed to the real

Black reggae.

Ali: I remember when I first heard them, I really didn’t think of any reggae

connection. Then so many people started saying about their second record, Reggatta de Blanc, “White Reggae,” everybody started calling it that. But it really didn’t

seem that reggae-oriented as far as I could see. I haven’t seen them live, but

I think I’d get bored. I like some of their songs, but (Sting’s) voice does

grate on the nerves.

FFanzeen: I

think he’s a better actor [laughs] [I saw the Police at the Diplomat Hotel when

“Roxanne” was a hit, and was incredibly bored; I totally agree with Ali about

Sting’s vocals – RBF, 2022.] What do you think of the style of some of the

other bands, like Adam and the Ants, and Echo and the Bunnymen?

Ali: I saw Echo and the Bunnymen, and I thought they were pretty good. Adam and the Ants; I like a couple of

their singles. I never thought they’d become as big as they did; but that’s

fashion. The Pirate. Malcolm McLaren (d. 2010) did it with Bow Wow Wow. He (even) told Adam how to dress. I think Bow Wow Wow are better, musically.

They’re a very strange band if you listen to them. The bass player’s incredibly

fast. There’s just one drummer and he can do it live. I understand from people

that he can get that sound live, where Adam and the Ants takes two drummers. It’s

been done before, with Gary Glitter and the Glitter Band.

FFanzeen:

Stiff Little Fingers’ lyrics are pretty political. Have you had any trouble

getting airplay because of them?

Ali: Whenever we play the U.K., our most requested song is “Alternative Ulster.”

It was the second single we did. It was on Rough Trade and Rough Digits, in

collaboration. It was banned at BBC. We sent it to them three times. It was up

for playlists three times, but they said no. We had to change the lyrics.

Whenever you send a single in, you have to send a single and you have to send a

sheet wit the lyrics on it. One of the lines is “RUC dogs of repression are

barking at your feet.”

FFanzeen: What’s

the RUC?

Ali: Royal Ulster Constabulary; Irish cops. Instead, on the sheet with the

lyrics on it, we had, “All you see are dogs of repression,” which is

practically the same, but because anything – anything close to home that might

be in any big way politically-oriented – there’s a complete clampdown from the

BBC. It’s ridiculous. I think that’s our most catchy single. It’s got a good

bass line, a nice guitar riff on it, but just because of the lyrics, they don’t

want to know. That’s censorship, you know? The BBC and the media over there got

pretty radical – they get more radical the further away from England. If there’s

anything close to home, right on their doorstep, you only hear what they want

you to hear. It’s worse over here, though. It’s like, if the Mafia pulled out –

if they stopped business right now – the whole U.S. would collapse. And

everybody knows it’s going on, but there’s never any mention of it, because

Reagan (d. 2004) eats jellybeans. I mean, there’s got to be somebody above the president.

As the interview

was winding down, Ali commented that he was feeling peckish. I asked him if he

had ever eaten sushi. He answered in the negative, but had been curious, so

Alan and I invited him to join us. We walked over to one of the better local

sushi houses at the time, Shima, the place where I was first introduced to sushi

by Dawn Eden Goldstein, which used to be on Washington Street near the old The Bottom

Line club (at the time, there was no proliferation of sushi bars, not even in

New York). It was an enjoyable dinner, and lively conversation about music and politics.

After the dinner, we all headed back to Irving Plaza. Alan and I were able to

walk in again, thanks to Ali. Thanks, Ali.

I managed to

see Stiff Little Fingers play twice, once at the aforementioned Irving Plaza,

and once at a sweat-filled, pogo-bouncing night at the Peppermint Lounge. I

came out as drenched as if I had stood under an upturned bucket of water. Both

times there was a strong energy level from the band and the audience equally.

They were great nights.

Stiff Little

Fingers broke up some time in the 1980s, and reformed without Ali (his choice),

who eventually rejoined, and they are still playing out today.

No comments:

Post a Comment